Artist Maria Timchenko was planning to open an art gallery to show her works in Kyiv when she found herself facing criminal charges for allegedly distributing pornographic content.

After someone shared her erotic paintings on the Telegram messaging app, the 37-year-old artist says she was looking at up to three years in prison and $1,800 for the distribution of pornography. Her plans shattered, she left Ukraine to settle in Germany.

Producing and distributing pornography is currently illegal in Ukraine. Broad interpretations of the law mean that even sharing a nude photograph with a partner can land a person in jail.

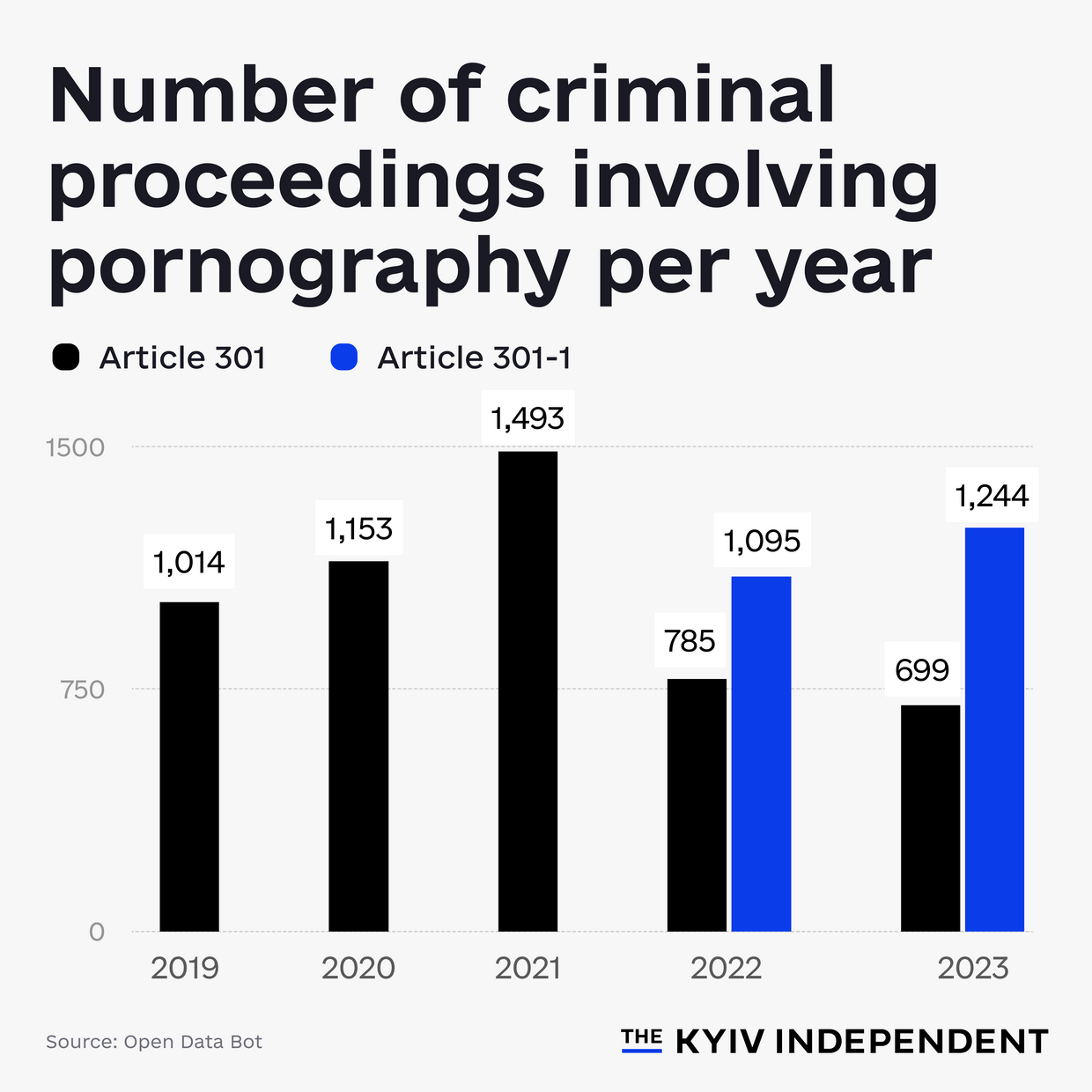

In 2023 already, 699 cases have been opened over the distribution, sale, and production of pornography, not including cases of child pornography.

In one case in July, a court in Poltava Oblast fined a woman almost $1,000 for sending two videos to her boyfriend. Meanwhile, in Sumy Oblast, a man was convicted to three years in prison with one year of probation for sending intimate photos and videos via a dating website.

Lawmakers and advocates say this has to change. In their view, the decades-old prohibition of pornography harms ordinary citizens by going after them for consensual sexual content, wasting state resources in the process.

The law is also economically backward given erotic content already generates revenue for the state budget despite being illegal, those who favor changing the law say.

OnlyFans, one of the world’s largest platforms for erotic content, has already generated more than Hr 34 million ($920,000) in tax revenue to Ukraine’s state budget from value-added tax in the first six months of the year, Ukrainian lawmaker Yaroslav Zhelezniak, who has been spearheading the latest effort to legalize porn, told the Kyiv Independent.

“It’s stupid to collect taxes for that and say it’s criminal at the same time,” Zhelezniak said. “If we decriminalize porn, it means less corruption and more taxes for the budget.”

A draft law submitted by Zhelezniak and other lawmakers from various factions in parliament doesn’t apply to child pornography, prostitution, or human trafficking – cases that should be the priority of law enforcement instead of private nude photographs, Zhelezniak says.

Potential millions in tax revenue

Dmytro Horiunov, an expert from the Kyiv-based think-tank Center for Economic Strategies says the “production of goods and services that don’t hurt anyone shouldn’t be banned nor prosecuted by the law.”

And business is good for the production of pornography.

OnlyFans generated just north of $1 billion in global revenue in the last fiscal year, with 15% coming from Europe.

The platform reported $5.55 billion in total spending by users, with creators taking home nearly $4.5 billion of that, according to a regulatory filing by its parent company Fenix International.

If, as Zhelezniak says, OnlyFans has already generated $920,000 to the state budget in taxes this year, then with a 20% VAT tax, OnlyFans’s content creators in Ukraine have made some $4.6 million.

“We estimate that tens of thousands of people (in Ukraine) actively work in this industry, maybe hundreds of thousands, from full-time on webcams to OnlyFans from time to time,” Ihor Samokhodskyi, head of the IT bureau at Better Regulation Delivery Office (BRDO), an independent think tank focused on reforms, told the Kyiv Independent.

A quick Google search shows that some agencies offer up to $2,000 a month in a studio and $700 a month at home for webcam models. Studios openly advertise in every big city in Ukraine, despite being illegal.

Based on the estimated number of people working in webcam studios, taxing the legal porn industry could bring billions of hryvnias per year to the state budget, Samokhodskyi estimated.

“The bottom threshold could reach Hr 1 billion ($27 million) in tax revenue the first year if studios come from the dark market to the legal one,” he said, possibly increasing up to $2.7 million per following year.

“It could bring billions of hryvnias in taxes over the span of several years,” he said.

Pornography is also popular in Ukraine. “We criminalize porn, but we are in the top 20 of Pornhub watchers,” Samokhodskyi said.

Abuse and waste of resources

The shadow market allows for all kinds of abuse from law enforcement authorities, from petty corruption to sexual abuse.

“We have problems with investigators who use it to control the shadow market and corruption is rising,” according to Zhelezniak.

“There are thousands of cases where policemen not only ask for money but also for sexual services” in cases involving pornography, he said.

Webcam studios have also been coerced into paying law enforcement officers for “protection,” extorting money from studio owners in exchange for the ability to continue working.

An investigation by Ukrainian outlet Zaborona back in 2020 showed that webcam studios are easy prey for blackmail from corrupt police officers.

Samokhodskyi and Zhelezniak believe fighting consensual porn and personal nudes is a waste of resources, and authorities need to get their priorities straight.

Law enforcement spent more than 80,000 hours over the span of the last year on cases of consensual porn and personal pictures shared online, according to Samokhodskyi’s estimates.

Ukrainian judges also tend to refer to the “International Convention on the Prevention of Circulation and Trade in Pornographic Publications,” turning 100 years old this year, to sentence people. Ukraine, however, never signed the convention after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The war shouldn’t stop Ukraine from reforming its approach to consensual porn, Samokhodskyi said. On the contrary, last fall, a petition for the legalization of erotica and pornography garnered the necessary 25,000 signatures for presidential consideration “when the war was even more active,” he said.

Horiunov said law enforcement doesn’t have the means to enforce the current law.

“There’s no chance for law enforcement to track (every case of pornography), and every time, a random person is going to be charged,” he said.

‘My body, my business’

Tax revenue aside, Zhelezniak says his main goal with this new draft law is to protect the rights of people for private life.

Oleksandra Mavka, a 26-year-old model taking part in the TerOnlyFans movement, told the Kyiv Independent that she supports the law because it increases liability for things like revenge porn and child pornography while allowing people to freely send intimate pictures to their partners or earn money from their content.

TerOnlyFans, a movement in which volunteers collect money for the military through nudes, has sent more than $866,000 to the army since its creation in March 2022.

The name is a play on words with OnlyFans but unrelated to the platform. Mavka says she got around the law by posting relatively “chaste” photographs.

The current law prohibits one’s free use of his own body that doesn’t harm anyone, she said.

Legalizing the porn industry wouldn’t just bring money. Ukrainian entrepreneurs and artists, such as Timchenko, could return home to pursue their work legally.

“I would like to return home, find a place for a gallery again, and develop erotic art specifically in Ukraine because it is about beauty, will, and desire,” Timchenko said.

“If I want to take pictures and distribute them, that’s my choice,” Mavka said. “My body, my business.”

For the moment, the fate of the porn industry in Ukraine remains in the balance. Polls from ZN.ua and RFE/RL show that the Ukrainian public is relatively divided over the issue.

Zhelezniak, for his part, hopes the new law will pass in the nearest month.

The article was published in The Kyiv Independent